What was always leaves a trace.

The trace is that which is both left behind, that which remains after, in the apres perhaps—maybe—appearing in the wake of what was, of what is no longer. It’s also, for Derrida, the what-is-to-come; l’avenir, in his words.

With Derrida, I read the trace as a holding-space of both what was and what is to come. The trace is an echo as much as a foreshadowing. Like Heidegger’s lichtung or “clearing in the forest”, it’s an opening, literally a space-clearing, or space-cleared. The trace is the stain, it is the echo as what remains, but at the same time it calls forth something not yet, or even just departed.

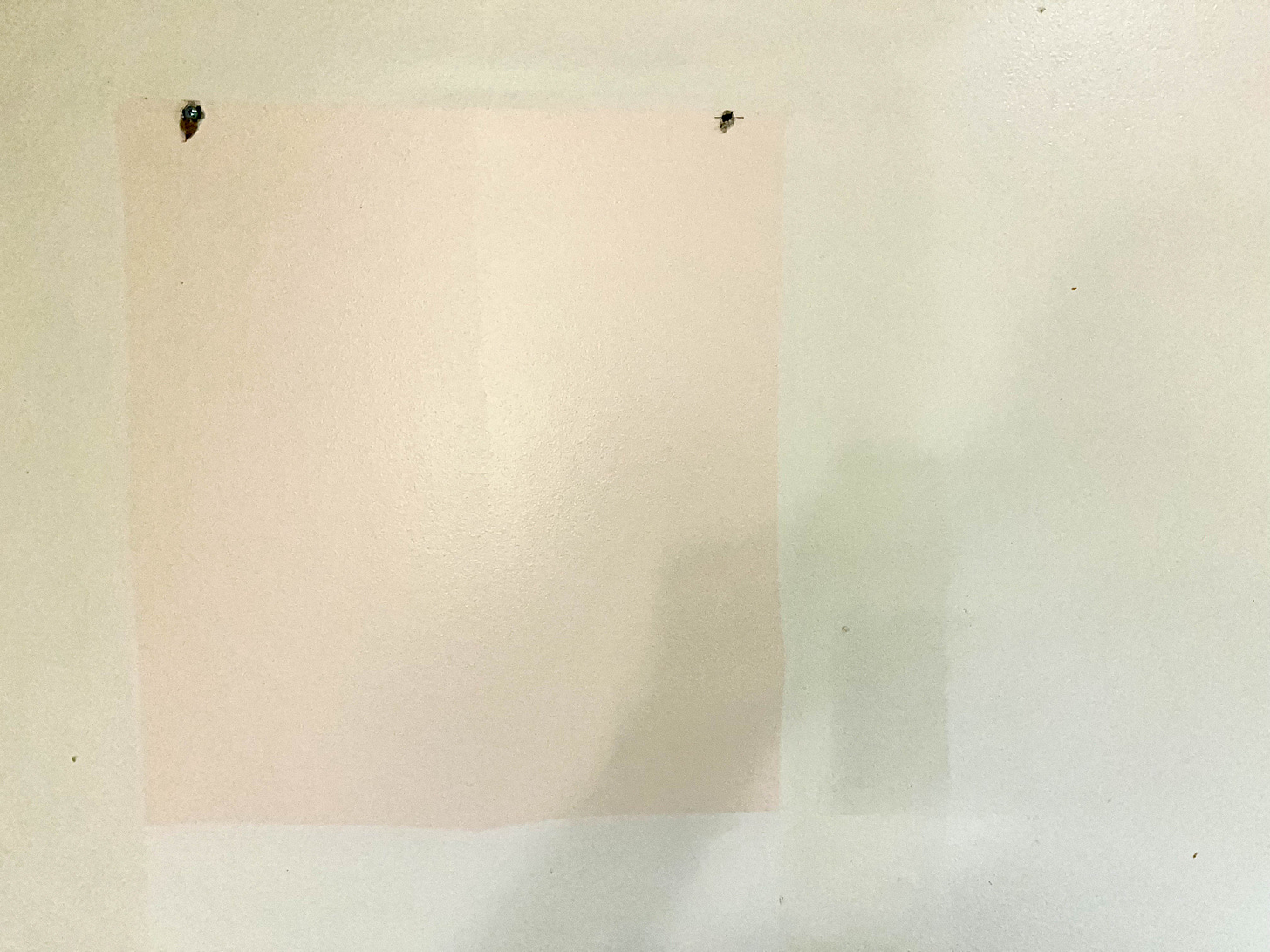

Something comes, some event happens, occurs. The trace is what happens in its already perceived absence; it is the presenced absence of a departure already underway. It is also an augury of a future not yet realized. It is the handprint, the smudge. The trace is oil. It’s greasy and adheres, metaphorically and actually. It’s traceable. It is a forensic. It is the streak against the windowpane, the dirty mark on the wall of the hotel room—almost not there and yet…

The trace is the warmed space of the already departed lover. It is the smell clinging to sheets, hanging in the stale morning air of the room. It is the sharp warm smell of of a just lit cigarette at the subway’s entrance. It is a dirty knife in a diner. It is always just gone, only hinted at, a reference, a pointing towards. It is faded paint. It is the fallen leaf, the spiderweb in the corner, the cicada’s carcass, the snakeskin, the slivered fingernail forgotten by the bathroom sink.

Always it is left behind, an object misplaced, forgotten, disposed. It is droplets of pee on the floor, a forgotten comb in a public restroom. It is a dream half remembered, suddenly.

The trace appears and comes (venir) in the departure of the thing. Within the departure is the French word departir: to separate oneself, to break into parts. The trace then is a parting, a separating of thing from what remains. Within our minds lay traces of memories—a child’s hand, the light on our childhood bedroom wall in the late afternoon, the duck eggs we gathered once, the voice of the mother, of the father, the vague memory of grandparents long dead, a grandmother with a cocktail turning in a kitchen by the sea, the memory of a friend dead too young dancing, a lover in Europe, an alleyway, a lingering meal in an orchard, a beer shared in an alleyway in Kowloon, a darkened street corner late at night, and my wife, not yet my wife, at a bar in a city long since abandoned. Each memory a trace, evidence of something not anymore, just gone.

(Not for nothing the Buddha in one of his many names is called the Tathagata, the one just gone. In the period before Alexander when Buddhism was still aniconic, the Buddha was always portrayed as just that—a series of footprints, an empty dais, the hint of something that was but is gone now—the trace).

And yet memory is present still as the spaces I move through in another city I once inhabited and feel my ghost on every corner, in every passageway. A memory which appears and seems to be a recalling—a calling again—towards a previous self. But it is as though that self had never left. Like Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, the self which was is still there, beckoning, calling out. I pass into that old self, reanimating it (the anima, the spirit), the trace a hint here, a prior world which attends and awaits, a pointing towards a past. The trace is unfulfilled desire. Not a sense to be consummated, to be had, but always as that which remains as a possibility—not a possibility in that it could be fulfilled, but as a possible other event. If each event, each moment, is one of a series of infinite other events which could have occurred but didn’t— this event happened but only because something else didn’t, in its place, replace it—that unfulfilled desire remains pregnant as possibility always.

This life, this gesture, the smile of a child, a marking on a wall, something said which lingers still, the Holocaust, the slap of the fathers hand against the child’s face, the violation but also the love, the brief shared glance between two strangers suffused with recognition, with possibility. All of it could have occurred and the trace is what’s left behind, and, perhaps, even, all of it did occur.

Leaving a trace: I wish I could share with you the photos of Passamaquoddy artist Jeremy Frey who makes exquisite baskets, beginning with the selection of the ash tree in the forest, the preparation of the ash strips, then the weaving, patient, slow, methodical, until the basket jar is done, reminding me of Wm Carlos Williams' poem "I placed a jar in Tennessee, And round it was, upon a hill. It made the slovenly wilderness Surround that hill." In the accompanying video, he set the jar/basket on a pedestal and then slowly, methodically, destroys it by fire until nothing is left but a trace. At the Portland (Maine) Museum of Art.