In the book on Landscape and Meaning by Richard Misrach, he writes that,

"In life, you're in motion on a path to somewhere. There's always momentum, but a photograph defies that linear quality of time; it stops us so that we can contemplate something we normally wouldn’t pay attention to.”

All The Lonely Places gives credit to the spaces left behind—to things in those spaces—forgotten detritus and objects, relations even—but also to the spaces themselves.

There is an analogy used in climate change studies about the coyote who is so focused on chasing the Roadrunner that he runs off the cliff, but hasn’t fallen yet.

The analogy is that we, as a society, have collectively run off the cliff and are just now becoming aware—now that it is too late. Wile E. Coyote is perhaps too trite to use, too simplistic, or even jejune.

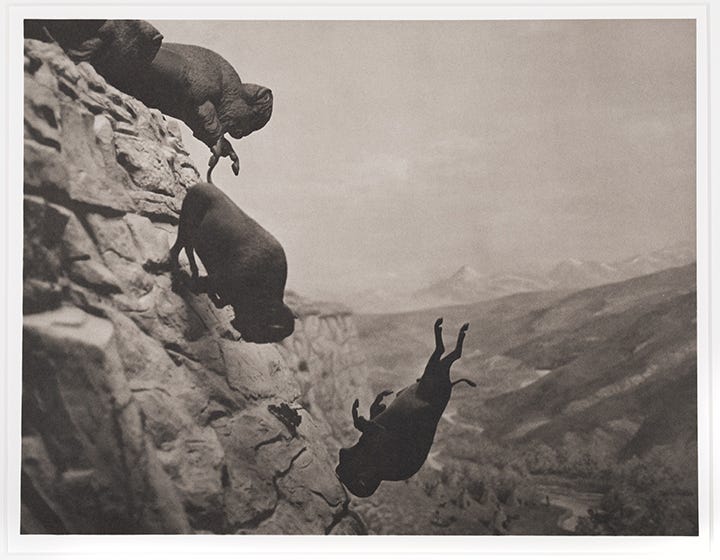

There is instead another image to use. This one from the late David Wojnarowicz —that of three buffalos plunging off a cliff.

Wojnarowicz used this image to illustrate the cover of his memoir Close to the Knives which describes his diagnosis with AIDS leading to his death in 1992, at the age of 37. The three buffalo—from a photograph of a diorama in a natural history display in Washington, D.C.— are in mid-fall, plunging to their death in the canyon below. Though just a diorama, they can be easily imagined to have been chased off the cliff in a desperate bid to get away.

The photograph describes just as well our own societal state. We have gone too far and are plunging over the edge. We—or many of us—haven’t collapsed —we aren’t lying broken at the bottom of the cliff (yet). These years of collapse capture us mid fall. But as the photograph shows we are headed towards that ruin, inevitably, just as inevitably as Wile E. Coyote will fall when he realizes that there is no ground left on which to stand.

All The Lonely Places holds itself in this moment—the moment before the collapse, the pregnant tension when we become aware of a future calamity. But instead of documenting what is to come, it looks back to what remains. It looks at, and even honors, what is left of unimpeded “progress”, whether measured over the last fifty years, or the last two thousand. It is the landscape and architectural equivalent of what happens after the machines are silent, after the clamor of progress has moved on, has become quiet.

All the Lonely Places is what the world looks like when we look away—it is a looking at what isn’t being looked at anymore.

Thankful to be in this moment, thinking with you.